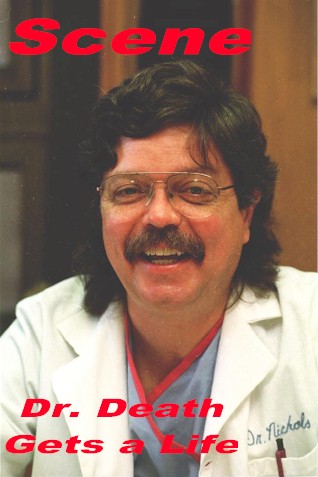

Scene Article

The following article “Dr. Death Gets A Life”, hit the stands following Dr. Nichols’ announcement to retire as Chief Medical Examiner. We would like to thank The Courier-Journal for allowing us to share it with you.

DR. DEATH GETS A LIFE

After nearly 19 years on the job, George Nichols sees the light at the end of the autopsy

Byline: C. RAY HALL, Staff Writer

Jan. 13, 1996

The subject is a white male, age 49, 5 feet 9 inches tall, approximately 160 pounds, with a history of gout and no distinguishing marks.

Well, no distinguishing marks except for this: It took Kentucky nearly 200 years to produce Dr. George Riley Nichols Jr. of Louisville. It could try for another 200 years without even coming close. Nichols is unique in the history of the commonwealth. Maybe even unique in history, period.

After nearly 19 years on the job, the only chief medical examiner Kentucky has ever had seems larger than life. And death.

He can perform a routine autopsy faster than Mr. Goodwrench can change your oil.

He has held and beheld the bones of President Zachary Taylor, looking for evidence of arsenic poisoning.

He has ventured into school buses that became coffins and coal mines that became mass graves. He has pondered death in its massive generality — 165 bodies at the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire — and its monstrous singularity — children murdered by their parents, or by other children.

He could have been the coroner to the stars, but quickly turned down the chance to become the medical examiner in Los Angeles. “If it’s hard enough to be the boss in Kentucky for 20 years, think how hard it would be to be the boss in L.A. for 20 weeks,” he said. “The office there does 10 times the number of examinations that are done in the Louisville office.”

No slouch at rhetoric, he incites it in others as well. “He’s the prince of sardonic humor,” said his friend Leo Lear. “He always has a comeback. It’s like he has scriptwriters.”

He cooks with amazing grace, and even more amazing regularity, but doesn’t mind feeding his children in neighborhood saloons known for their home cooking. (He and his wife, Dr. Janell Seeger, used to answer their youngsters’ pleas to go to McDonald’s by taking them to Check’s Cafe, near Eastern Parkway. Eventually, the kids got wise. They still call the place “McCheck’s.” And the boys really like the burgers and pint-sized pool table at the Bambi Bar on Bardstown Road.)

He’s been known to go into macho jock bars and exchange . . . recipes.

He won the heart of his mother-in-law, a Hoosier Methodist preacher’s wife, despite her initial horror over the cruel fiction that he likes to wear women’s underwear on his head. (A fiction created by her own daughter, Nichols’ future wife, as a joke.)

He’s an authority, more or less, on cooking, gardening and dogs (“Oh, bearded collies are a lot smarter than giant schnauzers!”). He can talk with anybody about anything, from asbestos to zoology. “He’s never out of his element. He is his element,” said Lear, who owns the Bambi Bar. “You can’t get over on this guy. He knows something about everything.” Said his wife: “He reads cookbooks from cover to cover, the way he reads the newspaper.”

He has helped his two oldest children, 12-year-old Ian and 10-year-old Dylan, perform an autopsy on a hummingbird. (Maybe the youngest should have gotten involved. When a pediatrician asked 5-year-old Jordan what his father does, the boy replied, “He pulls weeds.”)

In addition to weed-pulling, he teaches the boys to cook, drives them to soccer games and answers their questions about silicone-powered television actresses. (Nichols attributed their attributes to “better living through chemistry.”)

Testimony from his wife of 13 years: “He likes women a lot. He makes women feel good. He can make somebody who’s sitting alone at a party who looks miserable feel good. . . . He has that very pleasant ability to make women feel good about themselves.”

He might be the only Mercedes owner who also owns a T-shirt autographed by the pro wrestler The Undertaker and his manager, Paul Bearer.

He used to abide the nickname “Dr. Death,” until, he said, “Dr. Kevorkian screwed it up.”

He has an FM radio voice that seems incapable of uttering an unquotable passage. Here, for example, is Nichols on . . .

His craft: “The bitter truth is I can do an examination of a young, otherwise healthy male with a single medium- to small-caliber gunshot wound in his body . . . start to finish, slam-bang-thank-you-ma’am, in 18 minutes, with my brain on park and the emergency brake set. I’ve seen thousands of them.”

His busy season: “We have a six-week sprint from Thanksgiving till January the first. There are all sorts of things going on.

“No. 1, it’s darkest, and so you have driving errors. No. 2, you get brothers and sisters and other loved ones who don’t see each other very often in close proximity with each other and a weapon and an intoxicating substance. Third, you get an increase in drunken drivers.

“Fourth, we get a bunch of people who are chronically depressed who turn on the TV and they see that they’re supposed to be happy, and they become even more depressed and they commit suicide.”

His ability to carve up a human liver, then carve up a steak: “The important reason you take gross anatomy . . . is never voiced by the teachers. But the actual truth is, it’s to desensitize you, to make you from a normal, regular human being into a person who can leave a dead body or leave an appendectomy . . . and go eat lunch.

“After you live with a dead body for four months, what’s the big deal? That’s what you do as a freshman medical student.”

Higher math: “I have no idea how many (autopsies) I’ve done, other than a hell of a lot. I know I’ve done over 10,000.”

Pop culture’s leading lie about his craft: “That the coroner or medical examiner can determine the interval of death. Total and complex fabrication best described as the SWAG method. That stands for scientific wild-assed guess. . . . I have no idea when somebody dies unless I happened to be there when they were declared dead, or I did it myself. . . . Too many of us grew up watching Lt. Tragg (of “Perry Mason”) tell the court that this guy died at 10:30 p.m. Tuesday the 23rd. Wrong! Doesn’t work.”

Pop culture’s leading lie about violent death: “Sylvester Stallone and Bruce Willis movies, those things drive me absolutely nuts. People are instantaneously incapacitated. They never scream and cry after they sustain their immediately lethal injury. They are shot or struck and always are propelled backwards at least six feet — none of which are in any way close to what actually happens in real life. . . .

“Seemingly instantaneous lethal events — let’s say a gunshot wound through the heart? I’ve seen a guy run an entire city block with a gunshot wound through his heart.”

His job’s effect on his life and times: “I was cynical before I started. It has reinforced to me that Homo sapiens is not a nice species. Only guppies eat, devour or kill their children, until you get to Homo sapiens. Given the opportunity to be mean or inhumane, Homo sapiens will take every opportunity, especially if aided by the close proximity of a bottle of Jim Beam. We’re not nice. Compare us to the sharks: The sharks are saints.”

Tough talk for the former first trumpet player in the Atherton High School band. Maybe even tough talk for a former rock ‘n’ roller. In high school, he played trumpet and was backup singer in a band called the Louisville Falcons.

“We did what all the white guys did,” he said. “We imitated black guys. Who do you think we wanted to sound like? Somebody with real soul.”

Nichols needed little soul-searching to figure out his future.

“I thought I was going to be an American history professor at a small liberal-arts college someplace, with suede patches on my corduroy coat and a pipe in my hand,” he said.

But the Vietnam War intervened. History majors couldn’t keep student exemptions; medical students could. Nichols entered the University of Louisville medical school with lots of other youngsters worried about their futures.

“There are,” he said, “a whole bunch of draft dodgers in the class of ’72.”

As a medical student, he supposed he might eventually join his father, George Sr., in his family practice on Dixie Highway. But death reared its ugly head.

“One of the reasons I didn’t want to be a regular doctor,” he said, “was that I didn’t want to be around dying people.”

Dead people were another matter. Young Nichols became interested in forensic pathology, applying medical principles to death investigation. At the same time, Kentucky was revving up a statewide medical-examiner program to abet its hit-and-miss coroner system. (With 120 county coroners and uneven standards, some people were literally getting away with murder.)

David Jones, a former funeral director who was starting the program, liked what he saw of young Nichols and indicated he might like to hire him, eventually.

Nichols went to Cincinnati to learn forensic pathology. Even as a trainee in Ohio, Nichols joined in some Kentucky investigations. He was on the scene in 1976 after the Scotia mine explosions in Letcher County killed 26 men — 15 in the initial blast, 11 more two days later.

“That was one of the most frightening things that happened to me in my life, being in that coal mine,” he said. “There were people dead, eight along an underground railway as they were running out — three men blown into and through a concrete-block wall.”

The more he learned about death, the more he learned about life, and about the differences in the wide variety of people tied together by the word “Kentucky.”

“My trip to Scotia was really interesting,” he recalled. “I was raised as a Presbyterian going through the Highland Presbyterian Sunday school. The Protestant Christian God that I knew was totally foreign to the Protestant Christian God that the miners’ widows knew. The God I knew was a benevolent, cheek-turning entity that would forgive you for your sins and stupidity. . . .

“The widows had God the Punisher, who was there to seek retribution for your sins. . . .

“I found that out as soon as we got the bodies to the surface. There was immense screaming and yelling and shrieking — it was quite clear from their shouts and their screams that God was there . . . to punish for their sins — ‘Oh, God, don’t make him burn in hell too long!’ I was amazed.”

A year later, Nichols again was on the Kentucky side of Cincinnati, in Southgate, helping investigate the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire. Five weeks afterward, Nichols assumed his new job.

“Once he became the chief medical examiner, he became my boss,” Jones said. “So it’s the only time I know of in modern times in the commonwealth of Kentucky where a state employee hired his boss.”

Even before taking the job, Nichols had attended two disasters, Scotia and Beverly Hills. He might have been forgiven if he’d thought he’d seen the worst.

“Hell, I didn’t think about that,” he said. “I was 30 years old. Pumped up in my own self-worth. Thirty years old, chief medical examiner for the state. Well, of course, I was the ME’s entire staff.”

He was a staff of one, with a commission to go forth and multiply, with a political sensitivity that didn’t isolate and alienate the state’s coroners.

Dr. Larry Lewman, Nichols’ counterpart in Oregon, said, “He’s quite a remarkable guy. George came right out of his residency and his pathology training and . . . actually built that program. That’s a difficult thing to do for an experienced person that’s been in this business 20 or 30 years.

“Running a statewide death-investigation program is complex in that you have to be sort of a ‘bio-politician.’ You have to do forensic pathology, but yet you have to be able to develop, control and improve a complex statewide program. It’s particularly difficult because you have a hundred and some-odd counties. We only have 36 . . . and I’ve always got five or six that are driving me nuts.”

Nichols expects to step down next year, after 20 years on the job. He didn’t necessarily expect to stay this long, sort of figuring he’d eventually go to one of the high-powered jobs in some nameless Naked City. But when a job that once seemed a dream came his way, he decided to stay planted in Kentucky.

“Opportunity arose when Dr. (Thomas) Noguchi was relieved of duty the second time in Los Angeles,” Nichols recalled. “It took me about 2 milliseconds to say no.”

Nearly 19 years after Nichols became Kentucky’s one-man medical-examiner staff, the commonwealth has nine medical examiners performing about 2,200 autopsies a year. Five of the medical examiners are in Louisville, the others in Frankfort, Fort Thomas and Madisonville. Nichols said he is one legislative session away from adding another medical examiner and an autopsy technician, completing the quest he started in 1977.

“It takes patience to be a reformer,” he said.

After that, his wish list is short, but unlikely to be filled before he leaves office: a medical examiner assigned to southeast Kentucky.

“I could put somebody in southeast Kentucky and they would be overworked — just with murders. That is truly the murder capital of Kentucky. It’s tough down there right now. When I started, it was Breathitt County. But those guys are either all dead or all in jail. Now it’s moved” — to Whitley, McCreary, Knox and Clay counties, he said, adding, “In the last year Pulaski County has had a lot of murders.”

The rub: finding someone qualified or trainable who is also willing to live in, say, London, Ky. The training would take five years. And Nichols has less than 18 months before retiring.

“Twenty years and I’m out,” he said. “I’ve said that for the last 10 years. Twenty years as a chief of anything is an extraordinarily long time. You’ve made so many decisions that it’s time for somebody else to step up and face the music.”

He points to a quote from Reggie Jackson, the baseball player, stuck to his office door:

“It’s hard to be ‘The Guy.’ You need perspective, you need to be able to step away. When everything you do or say is the story, it wears you out mentally. You have to control it, or it will control you. You must make time for your family, your friends, or find the time to be alone and be yourself. Without that, the burdens will eat you up.”

The remarkable thing might be that Nichols has made it so far without being eaten up.

Dr. Greg Davis, one of Nichols’ trainees who is now a medical examiner in North Carolina, said, “He is somebody who has always recognized the emotional toll that cases can take on forensic pathologists. . . .

“There’s a phenomenon in our profession where sometimes you get people who, because they’re either macho or incredibly insensitive, deny the emotional toll that these cases take. Those are the people who become eccentric to the point of being ineffective. Whether they drown their feelings in alcohol or quit after five years, it gets to them and they become ineffective. George’s health in this respect comes from his always acknowledging it.”

Davis recalls a signal event: the 1988 Carrollton highway tragedy, in which 24 youths and three adults died when a drunken driver’s pickup truck struck their school bus as it returned from a church outing.

“To a lot of folks that don’t know him, he’s sort of an irascible fellow, or seems to be. He’s got a sardonic wit; he seems to have sort of a cavalier attitude toward life.

“That’s for people who don’t know him.

“You scratch that veneer — that veneer was mauled during the bus-crash tragedy — and what you see underneath is somebody who feels very intensely and very deeply.

“I know from conversations with George that he was markedly changed after the bus crash. I think being the first person on that bus and seeing the effects of what that drunk driver did had a profound effect on him. . . .

“I know he had some troubled dreams for a long time. . . . While I don’t think it changed his decision to retire after 20 years, I think it certainly may have reinforced it.”

At Carrollton, Nichols slammed head-on against one of the cruelest ironies of his business, in which there are no consolation prizes. What might have been his brightest hour was also one of his bleakest.

“George was incredible — the manner in which he was able to go into that bus, arrange things, to actually have the bus moved from the interstate to the National Guard Armory was a stroke of genius. He took a crime scene, which was that bus, and had it moved, which I don’t think a lot of people would have had the smarts to do.”

“I don’t know if I could do that one again,” Nichols said. “That one used up a lot of emotional reserves. . . . We were in (the bus) for hours, and you were constantly reminded of the multiplicity of death. We had to literally unwrap these kids from each other.”

Said David Jones, the man who hired him: “For one of the few times, Dr. Nichols was forced into dealing personally, one on one, with all the families. . . . He faced these families, he heard their crying and their anguish, and he more or less was that person telling them, ‘Look, you all have just got to face it: Your kids are dead.’

“To this day, Dr. Nichols does not like to talk about Carrollton. If some group, even in some other state, wants someone to talk about that, he usually calls me and I make the talk.”

Nichols recalls the heartbreaking example of Bobbie Ritter, an admired autopsy technician who worked closely on the case.

“She went from being the strongest woman I had ever met to being a woman who had aged dramatically after that. She was used up and spent. I don’t want that to happen to me. There are only so many Carrolltons of life that you can tolerate. . . . How many times do you see 24 dead kids?

“You can only take so many kids, because that gets you. The same thing happens to pediatric intensive-care doctors. They can be there only so long before they have to get out. Either that, or you develop a wall of inhumanity as self-protection.”

The following year, another career case came crashing down around Nichols and his staff. He and two associates were working a mine disaster in Western Kentucky. Upstate in Louisville, Joseph Wesbecker entered the Standard Gravure printing plant armed with guns and grievances. He killed eight and wounded 12 others before shooting himself to death.

Janell Seeger saw Carrollton in her husband’s face again.

“I thought he was going to quit,” she said. “He came home and ranted and raved and took all the kids’ toy guns and threw them outside and stomped on them. There are only so many disasters you can absorb.”

As chief medical examiner, Nichols is involved in cases all over the commonwealth. Tom Handy, the Laurel County commonwealth’s attorney who recently ran for lieutenant governor, recalls Nichols’ contribution to a puzzling murder case.

“We had a lady who had been beaten over the head eight times to where the cranium just separated; it fell apart once they started doing the autopsy. In addition to that, she had been decapitated. We had enough blood in the room in which it took place to fill a teaspoon.

“Question: How can that brutal attack take place and have no more blood than that? She’s found in a barrel and there’s a very limited amount of blood in the barrel. The defense was hinging on that, that the murder took place somewhere else.

“It was a difficult problem. What George found was that there had been a ligature around the neck which cut off the carotid artery. He further established that there were bruises on the torso . . . showing a collection of blood running and it terminated there. . . . No blood flowed upward (to the brain).

“It blew them out of the water and made a very good case for us.”

With more than a year left on the job, it might be too soon to talk about Nichols’ legacy. But maybe not.

“He demands excellence in the entirety of the office,” Handy said. “I believe he has got the standards up so that Kentucky, though we may rank bottom in a lot of things, we don’t rank bottom here.”

The strongest legacy might come in the way Nichols affects those around him. Nobody feels it more strongly than Davis, the North Carolina medical examiner who studied under Nichols from 1986 to 1991.

When Davis finished his residency, Nichols gave him a collection of medical illustrations. On the inside cover, Nichols wrote: “Maintain your enthusiasm. Always be truthful.”

It’s a recurring theme.

“He is really very exceedingly honest . . . just very moral in his attitude about his job,” said his wife, a cancer specialist. “It took me a long time to realize that he never says who did something; he just says how it was done. He doesn’t get particularly attached to the outcomes. . . . If the jury says ‘not guilty,’ that’s not his problem.”

In the not-so-distant future, Nichols faces a life without autopsies, without court testimony, without asking legislators for money. After being immersed in dead bodies for 20 years, what’s a man to do?

“He can buy my bar and immerse himself in dead minds,” cracked Leo Lear, who owns the Bambi Bar.

“He’s such a multifaceted person that I know he will not be bored,” Davis said. “He’s a fanatic about water sports and boating. I can almost see him spending a lot of time in the Gulf of Mexico or the Caribbean. With his personality, he could open a restaurant, a pub, something like that, and be wildly successful.”

“He says he’s going to write a book and stay home and cook,” said his wife.

“I could do a lot of things,” said Nichols, who could expand his private-pathology practice or become a full-time professor at the University of Louisville. “One thing I know I’m not going to do is become a regular doctor.”

Or, it seems safe to say, a regular anything.

Body of evidence: all in a day’s work

Fifteen hours ago, the middle-age woman was as alive as you and the other 6 billion people on the planet. Now she is lying on a stainless-steel table, waiting to tell her last secret. It’s possible that cocaine overloaded her heart, delivering her to a hospital emergency room, then to the hereafter.

With her left eye half-open, she looks groggy, as if she might wake up at any moment, wondering how she landed in a long white, windowed room on the seventh floor of the old Kentucky Baptist Hospital, beyond heavy swinging doors warning “Security Clearance Required.”

Jason Ritter, a pleasant young autopsy assistant, stands behind her head, which is perched on a tiny stool. Atilla Omeroglu, a young doctor from Turkey who is learning pathology, is at her feet, ready to section the organs for lab samples. Dr. George Nichols, wearing a light blue surgical scrub suit and dark blue Nike running shoes, stands beside her.

“We are going to take these scalpels, and we’re going to make a series of incisions,” Nichols tells an observer. “I will tell you that you will see things you’ve probably never seen before. You undoubtedly will smell things that you haven’t smelled before because we smell like people inside, whether you’re alive or dead.”

Nichols begins his monotone narration for an overhead recorder: “Hair is of normal texture . . . petechial hemorrhages are not seen . . . periodontal disease is prominent . . . rigor mortis is well-formed . . . a crude monochromatic tattoo . . .”

Although her face looks alive, if slightly punchy, her torso is obviously lifeless and pitifully compliant as Nichols and Ritter cut a large Y in her chest. In seconds, she is open, revealing a thick cocoon of yellow fat between her skin and her organs, which are shades of maroon, gray, yellow and pink not seen anywhere else.

“The first time one sees the inside of Homo sapiens, one is amazed at what we actually look like,” Nichols said. “Usually the first thing everybody says is, ‘Is the liver that big?’ and ‘Are we that fat inside?’

“Even first-time med students . . . because all they’ve seen is pickled people, they’re amazed at what the textures are like when they feel it, and they’re amazed at the colors.”

As Ritter prepared to saw the skull open, Nichols said, “This is what I refer to as the ‘banjo of the morgue.’ This is the same saw that is used to cut off a cast. It’s an an oscillating rotary saw. Goes back and forth real fast. Will cut through hard stuff but won’t cut through soft stuff.”

With a grating, high-pitched whir, the saw bisects the skull, allowing for removal of the brain.

“This is where you live,” Nichols said, holding the gray, wrinkled brain in his hand after weighing it.

With her scalp bisected crosswise, a flap of skin is pulled forward, covering the woman’s eyes, as if to shield them from the gore before her. The skin covering her torso is pulled aside like an enormous coat; there’s a deep, glistening pool of wine-red blood in her chest, where Nichols removed the heart before passing it to the young doctor.

“Give me lots of sections of heart in the save bucket there, Atilla,” Nichols said. “I need more.”

The heart sections look like little filets, leading to the discomfiting awareness that humans are, at some basic level, meat.

As Nichols works in the chest, there is no odor. But when he gets to the gut area, the smell is sour, overpowering. It makes the eyes water and the stomach tumble. But, by autopsy-room standards, it’s fairly benign. Across the hall, there’s a room labeled DECOMPOSED. (“You don’t want to go in there,” Nichols said.)

Larry Austin, a deputy coroner, seems like a smart guy to be standing in the doorway, visually in touch, but in nasally neutral territory. A helicopter whirs across the sky, getting his attention as it heads for one of the downtown hospitals a few blocks away.

“That’s one of the trauma helicopters,” Nichols said. “Also known in the medical business as a hovering hearse, or a mobile morgue.”

Working so close to so many dead people, isn’t it hard for folks in Nichols’ profession to stay healthy?

No, he explained: “The real simple things to explain about good health are the following: Don’t overdrink, don’t overeat, get some exercise and wear your seat belts. Because we see the results all the time of overdrinking, overeating and not wearing your seat belts.”

The organs, minus tissue samples, are returned to the body. Thirty-five minutes or so after the first incision, Ritter is sewing up the woman’s gaping torso with coarse cotton suture. He covers her with a white sheet and wheels her toward the cold-storage room. Her next ride will be to the funeral home. Seeing her in the casket, mourners will be unable to guess at the disarray that attended her earthly remains hours ago.

She will have been long buried by the time the lab results tell the cause of death in three weeks or so. If cocaine killed her, Nichols tells how: “If you want to short-circuit your ticker, crack cocaine is a great way to do it,” he said. “You either end up having a seizure and dying of that, or you have your heart rate go up to about 3,000 and it can’t pump anymore. Which is what looks like happened to this lady. She’s got plenty of blood, and it’s not really in an abnormal location; it just hasn’t been moving briskly enough through the organs.”

As Dr. L.C. McCloud, another medical examiner, prepares to perform the next autopsy, Ritter wheels the subject – a middle-age man who died in prison – toward the autopsy room.

Seeing the evidence of rigor mortis beneath the white sheet, Nichols said, “this guy’s been dead awhile, huh?”

Copyright 1996 The Courier-Journal

Photos by Pam Spaulding

2006

2016